In the past year, China has been ratcheting up repeated attempts of targeted harassment towards drilling operations being conducted by Malaysian oil exploration ships and escorted by Malaysian Coast Guard and Navy ships within Malaysia’s maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Such actions have largely been perpetrated by relatively large numbers of Chinese Coast Guard vessels escorting a nominal government survey vessel, supposedly in the regional waters for resource exploration purposes but in reality a flag-waving exercise to show Chinese maritime presence in the contested maritime territories of the South China Sea.

The latest incident ongoing off the Bornean Coast has attracted sufficient regional attention that the US and Australian Navies have both sent combat vessels of various importance to conduct joint naval exercises in the immediate vicinity of both Malaysian and Chinese vessels. Both Western naval powers firmly support Malaysia’s maritime posture in defending her sovereign rights on the high seas and maritime territories.

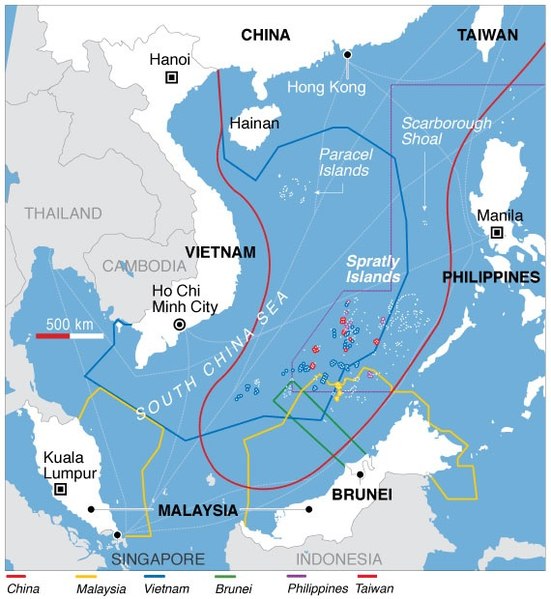

Whilst the South China Seas territorial disputes over issues such as the Spratly Islands and China’s unilateral “nine dash line” territorial claim do not directly impact on any territory held by Singapore, there are clear and present concerns that make any developments in the South China Sea immensely impactful and influential on the national interests of Singapore.

Being a city-state situated on the tip of the Malayan Peninsula and astride the busiest shipping trade route in the world, Singapore’s national fortunes depend heavily on the lifeblood of international maritime trade passing through her port as they shuttle between Europe, Asia and Oceania.

As an important entrepot node of international free trade, it is entirely in Singapore’s national interests that the maritime commons internationally, and particularly on her doorstep in the South China Sea, exist in a peaceful condition, with minimal to no territorial expansion or militarisation by any regional power.

Singapore’s dependence on international maritime trade is also an important reason motivating its international diplomatic stance as a Non-Aligned state.

Whilst the city-state is nominally aligned to the US and the West in terms of defence cooperation, Singapore also has to navigate the sometimes choppy waters of diplomacy and engagement with neighbouring countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia. Most importantly, it must also keep good relations with Beijing, with the bulk of its exports made to mainland China (13.2% at US$51.6 billion) and the Hong Kong SAR (11.4% at US$44.4 billion).

Since 1970, Singapore has been part of the international Non-Aligned Movement, which espouses policies and multilateral cooperation initiatives, so as to provide mutual benefit for all parties involved. Such an international diplomatic posture has been beneficial and sustainable on the global maritime commons even during the Cold War era thanks to American hegemony on the global maritime commons.

ASEAN in its current form remains weak and divided, ironically because all its member states are also non-aligned states and thus susceptible to great power lobbying

However, as China rapidly grows in military, economic and political status to challenge American maritime and political hegemony in a post-Cold War unipolar world, its appetite for historical revisionism and flexing of renewed maritime interests in the Asia-Pacific is growing exponentially.

This comes at the cost of all maritime countries with coastlines and territories bordering, or existing within the South China Sea, a region which Beijing wishes to exert naval and economic dominance over as its own backwater and strategic buffer in a growing zero-sum power struggle with the US over who remains the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific theatre.

ASEAN in its current form remains weak and divided, ironically because all its member states are also non-aligned states and thus susceptible to great power lobbying. With the exception of Singapore, ASEAN member states are generally considered “weak states”, characterised by a lack of political and social cohesion.

This makes intra-ASEAN political, defence and security cooperation more difficult. Moreover, it was only till recent years that ASEAN member states had vastly differing perceptions of threats from China, which only growing Chinese naval dominance and unilateral actions in the South China Sea have managed to slowly crystallise into a relatively unified view.

Taking advantage of the fractured and non-aligned postures of ASEAN maritime states, China has managed to strong-arm and stall intra-ASEAN cooperation and unity in negotiating and dealing as a unified regional bloc against a regional great power such as itself.

Under such circumstances, the role of the US in the Pacific gains even more importance for the future of the region in terms of trade and encroaching militarisation.

While the US is not a ratifying state of UNCLOS III (United Nations Convention on the Laws Of the Sea), an international maritime treaty governing maritime territorial claims and freedom of navigation rights, it shows far more respect and emphasis on respecting maritime territorial claims, protecting and ensuring free maritime trade and navigation globally than the PRC, who is a ratifying state of the treaty.

It is therefore vital for ASEAN’s non-aligned member states to gain the support of the US in challenging and pushing back against encroaching Chinese maritime demonstrations of power and territorial claims, even if this means the abandoning of non-alignment as a diplomatic and political posture for these states.

In a conflict between two great powers, to stay neutral is to expose oneself to great power manipulation and bullying to sway support in favour of their respective positions and motives.

Singapore should leverage on its position as the most Westernised and US-aligned country in ASEAN and the South China Sea to help drive home the message of cooperation and choosing a side for ASEAN member states. ASEAN won’t stand a chance against China even in its most united state given current circumstances, hence it is imperative that it casts its lot in with the US in the growing power struggle in the Asia-Pacific theatre.

There is no contest between which major power would respect and maintain the status quo of open, free maritime trade in the South China Sea: only the US will guarantee that.

No matter what the cost of Singapore and ASEAN has to pay in showing itself to be an equal aligned regional bloc to the US in terms of military and political cooperation, it is surely far smaller than the ultimate cost of surrendering the South China Sea and maritime free trade there to the diktat of China.

Andy Wong graduated with a Joint (Hons) Politics and History degree from the University of Hull, UK in 2017. He currently resides in Singapore and is a freelance defence and current affairs analyst. His main specialisation is in maritime security, naval warfare and Asian-Pacific geopolitics.