In mid-November, Pascal Tanguay attended a meeting at the Palazzo Hotel, a stately, modern boutique smack dab in the middle of the Thai capital Bangkok. During the meeting, several people – three, he estimates – overdosed on heroin they had taken during a coffee break. There were no deaths, but everyone was shaken.

At the meeting – organised by the Ozone Foundation, an organisation that facilitates community-based health service access for drugs users – was Somchai*, attending with fellow members of the Thai Drug Users Network. Many of the members of the awareness group, which was formed in 2002, hadn’t seen each other in over a decade.

During a break, Somchai pulled out heroin he had purchased from his usual place in Sukhumvit – the infamous home of Bangkok’s red light district and nightlife – and passed it around. The high hit him harder than usual, but he was fine. Somchai’s friend, however, slumped in a corner, overcome by the drugs.

He was only revived using the naloxone kit someone miraculously had on hand.

Once everything had calmed down, Tanguay, who has worked in the harm reduction sector of drug policy for 16 years, had a nagging instinct that something wasn’t right, and proposed testing the drugs with kits he had at home.

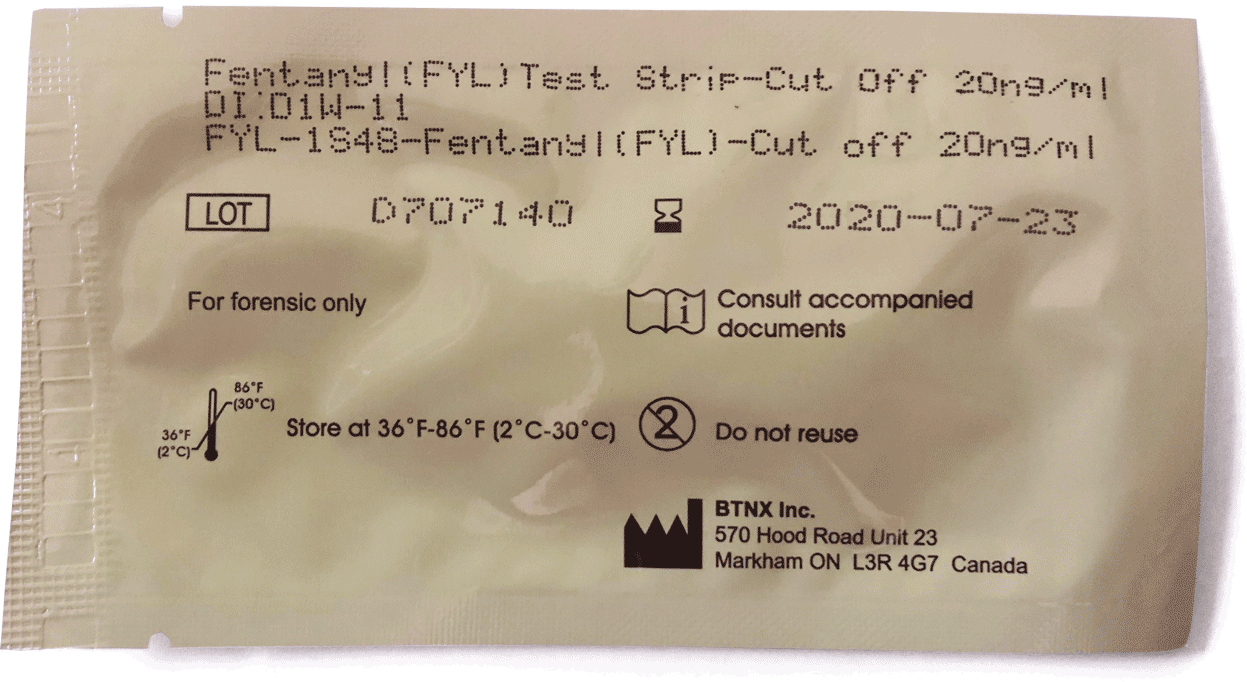

Hunched over a table in his small painting studio the next morning, careful not to get any on his hands, Tanguay shook out a bit of the heroin into a divot on a sterile plastic paint palette. He dripped water into the makeshift cup, carefully stirring it, before coating a blue and white test strip with the mixture.

After 30 seconds or so, one red line slowly appeared on the paper strip, and the gravity of the discovery was immediately evident to Tanguay. The drugs contained fentanyl, the synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine, responsible for thousands of overdose deaths worldwide each year.

“I was surprised, because to date, there’s been very limited fentanyl discovered in the drug supply in Asia,” he told the Southeast Asia Globe. “Some colleagues told me that they had identified some fentanyl in Indonesia and India, but no one in Thailand had ever mentioned to me the presence of fentanyl in the drug supply.

“So this was kind of a first, but … it was eventually going to get here. I’m terrified of this.”

Somchai, one of those who had a lucky break that day, said based on the feel of his body, current batches of heroin are “totally different” from what he’s been using for the last year, with the overall quality downgrading.

“I already assumed that it would have something in it,” he said, adding that he is careful not to fall asleep on this newer variation.

The 54-year-old now works as a freelancer advocating for drug policy reform, but has never had adequate resources to shake his addiction, nor has he really wanted to. He is also frightened, but not for himself.

Somchai said that he has built up a large tolerance for opioids through a decade of using heroin; he also smokes marijuana on occasion, and takes amphetamines and yaba – a mixture of caffeine and methamphetamine – sporadically. But people with lower tolerance like his friend – a once-a-month heroin user Somchai estimates – are in more serious danger.

“I’m scared of giving it to my friends. Who knows if they are going to die?”

No statistics, no clue

The discovery stemming from that November meeting in Bangkok affirms the once-distant nightmare of policy-makers, advocates, and drug-users: that fentanyl is making its way into the street drugs of Southeast Asia, a region wholly unprepared for it.

Jeremy Douglas is the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) regional representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. With work that takes him from Asia’s bustling urban centres to rural communities – with a lot of focus placed on methamphetamines, heroin, and ketamine – he has long been an advocate for forward-thinking when it comes to regional drug policy.

“Nobody knows for certain,” said Douglas, when asked if this the first time that fentanyl had been uncovered in Thailand. “It is basically impossible to know without testing drugs, and the region has not been looking.”

However, he cautioned that it is unlikely fentanyl was only in this one batch of heroin, and is likely more widespread.

“We expect it to come, if it hasn’t already.”

But with a dearth of knowledge among the general public and the government about fentanyl entering the drugs market in Thailand, and the region as a whole, it’s hard to address the issue, and hard to save lives.

Even if fentanyl is seemingly seeping into street supplies of other drugs, it’s not clear that authorities and policy-makers know about it. Few countries in Asia track drug use, treatment, or overdoses in any fulsome way, and the majority of the time when someone overdoses there is no follow up testing of the drugs or support, especially if that person is low-income or marginalised.

“The reality is that countries in the region largely understand the drug situation from a law enforcement perspective, and even then it is largely seizures and arrests and not strategic analysis of the situation,” Douglas said.

It is simply good business for organised crime, who are in the business of turning a profit – and with fentanyl the profits are massive, far larger than with heroin

Jeremy Douglas, UN Office on Drugs and Crime regional representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific

At the same time, infrastructure is perfectly laid out for fentanyl to infiltrate existing drug supplies.

The borders of Myanmar, Thailand and Laos have been associated with drug production and trafficking for several decades, but the levels of synthetic drugs being traced back to the area, Douglas explained, is unprecedented. The high pre-existing demand for heroin means that opioid dependence is built into the region – and as Somchai testified, fentanyl, both laced and pure, feels more addictive.

Adding to Fentanyl’s threat is that it is much cheaper to make than other drugs, and its synthetic nature means that setting up and moving production sites is relatively quick and painless. In contrast, the vast poppy fields needed for heroin are easily identifiable and cannot be transported.

“It is simply good business for organised crime, who are in the business of turning a profit – and with fentanyl the profits are massive, far larger than with heroin,” said Douglas. “It is a matter of when it happens, not if it happens … traffickers literally use Southeast Asia as their playground.”

Driven underground

For years, the US has cited statistics showing Chinese supplies of fentanyl flooding the market, with 97% of the drug seized from international mail services by US law enforcement in 2016 and 2017 coming from the country.

“[Chinese President Xi Jinping] said he was going to stop fentanyl from coming into our country. It’s all coming out of China. He didn’t do that,” US President Donald Trump said in August.

But China is now slowly shifting its approach, and over the past year the country has taken steps to better investigative and legislate the drugs used as the building blocks for fentanyl, which often escape detection.

However, Roger Bate, visiting scholar with the American Enterprise Institute and a researcher on international health policy, speculated that the stricter legislation, meant to protect the US from shipments of illegal narcotics, could very well displace fentanyl production and shipping from China to Southeast Asia.

The main effect, he argued, will be to drive fentanyl production in Asia further underground, spreading production and use to low-income countries without the means or the political power to combat it.

“Beijing certainly would need to spend a lot more effort to track down production of these chemicals if it really wanted to change things,” said Bate. And even if they did, he explained, fentanyl’s flexibility means illegal producers and traffickers can easily adapt – perhaps even using large Chinese diasporas across Southeast Asia to develop production sites and markets.

North America’s own overdose crisis – which has soared over the past decade, largely driven by fentanyl – provides a bleak vision of its potential impact on Southeast Asia if this were to occur. Even with Canada and the US’ early warning systems, sophisticated communication across regions, and public health authorities with resources and community support, deaths have been rampant. In the US alone, more than 30,000 people died in 2018 after overdoses involving fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

Southeast Asia, too, is bracing for impact. In mid-November, the Mekong Memorandum of Understanding on Drug Control (MoU) signatories – Cambodia, China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam – met for two days of discussions and negotiations following “recurring reports of significant increases in the production, trafficking and use of illicit drugs” in the region.

According to Douglas, in attendance at the meeting, the countries agreed that drug prevention and treatment needed more priority, with the region’s current punitive approach not working. But with limited resources or time devoted to the cause, the governments’ focus remains overwhelmingly on the drugs that have already overtaken the region, rather than emerging threats like fentanyl.

“With all its capacity North America was not ready, and Asia certainly is not,” Douglas said at the meeting’s conclusion.

Crackdowns won’t crack it

Southeast Asian drug policy is famously violent and unforgiving. Most notably, Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte’s infamous “war on drugs” since coming to power in mid-2016 has resulted in the deaths of over 12,000 Filipinos to date.

Eamonn Murphy, regional director of the Asia-Pacific branch of UNAIDS, said in a recent op-ed co-authored with Douglas for Filipino newspaper The Inquirer, that this current approach of criminalising people who use drugs just drives them further to the margins of society.

The point is that the war on drugs is not helping us at all. It’s a war on people, it’s a war on the drug user … more than a war on drugs

Somchai

They highlighted the more than 455,000 people who use drugs who have been held in “compulsory detention” – enforced treatment conducted in conditions similar to prisons, but without due process and judicial review – across Southeast Asia in recent years.

“If we want to stop the drug use, you need to help the person deal with it from a public health point of view,” he wrote, adding that removing the stigma from drug use in Asia would allow other epidemics sprouting from the crisis, like HIV, to be combatted simultaneously.

Experts say the decriminalisation of people who use drugs could help achieve this, with Southeast Asian users often on the extreme margins of society, with little, if any, social support.

In January, the International Crisis Group said “education and harm reduction should replace criminal penalties for low level offenders” as they made recommendations for Myanmar’s Shan State, a hotbed of poppy fields used for the production of heroin.

Douglas said that without harm reduction at the forefront of efforts, effectively tackling the widespread impact of drugs is unlikely.

“Everyone wants to talk about the drug scourge … Nobody wants to talk about the user.”

For Tanguay, who uncovered the fentanyl in the heroin used at November’s meeting in Bangkok, it was a miracle he had access to the testing strips at all. He said his kit was a remnant of a project he worked on with the Asian Network of People Who Use Drugs a year earlier, shipped from an American NGO.

Moreover, if the overdoses that day hadn’t happened in a room full of advocates and policy-makers with a naloxone kit on hand to revive his friend, he may have died and fentanyl would likely never have been determined as the cause.

But naloxone kits, which are regularly distributed by pharmacies, nonprofits and other groups in North America, are nonexistent in the public health sector in Southeast Asia.

“Drug checking is not integrated in the harm reduction response in Thailand – or anywhere in Asia, for that matter,” said Tanguay. “The combination of the absence of peer-to-peer naloxone distribution, and the absence of drug checking, is the perfect recipe for massive increase in overdose deaths like what we’re seeing in North America and Europe.”

As a person who uses drugs, Somchai would prefer easily available naloxone kits for reviving overdosers, rather than test strips to check drugs for fentanyl. He explained that even if he knew fentanyl was in the drugs he was taking, he would likely take them anyway, and that many users feel the same.

But making naloxone kits readily available in Southeast Asia – and in general, a more holistic support system for people who use drugs – looks a long way off. Tanguay says he thinks “it’s going to take several years, if not several decades”.

With fentanyl seemingly creeping into the region, and all the associated risks of lethal overdoses that brings, time is ticking.

“The point is that the war on drugs is not helping us at all,” Somchai says. “It’s a war on people, it’s a war on the drug user … more than a war on drugs.”

*Name has been changed at the request of the interviewee