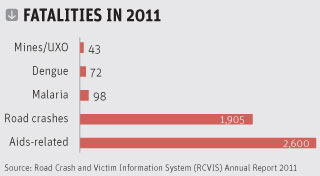

What kills Cambodian people? Most observers trot out the usual suspects of malaria, dengue fever, Aids or landmines. Traffic accidents rarely get a mention, but close to 2,000 people died on Cambodian roads last year – nine times more than malaria, dengue fever and mine victims combined. This death toll has doubled in the past seven years and without the required action from authorities, it could exceed 3,000 fatalities a year by 2020, according to the new Cambodian RCVIS (Road Crash and Victim Information System) annual report.

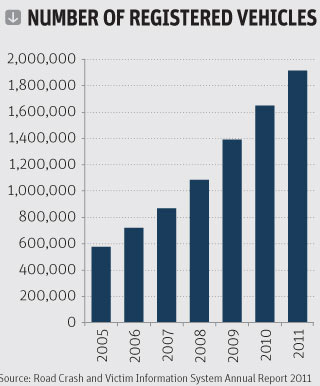

This upsurge in road crashes is something of a new development in Cambodia. In less than ten years, the number of vehicles on the Kingdom’s roads increased from 300,000 to almost 1.6m, with that figure expected to rise to 4m by 2020. While more and more Cambodians splashed out on vehicles, the muddy road network was rapidly replaced during the same period by paved tracks and tarmacked roads, allowing cars and motorbikes to reach speeds hitherto unknown in the country. It has proved a deadly cocktail, immediately translated by the explosion of casualties in national statistics.

This alarming trend is common in many poor countries. According to the Asian Development Bank, low- and middle-income developing countries now account for 50% of the world’s motorised vehicles but already suffer 90% of road crash fatalities.In Cambodia, past political decisions partly explain the current road problem. Following years of conflict and delayed economic development, authorities expended all their energy on boosting transportation and trade as quickly as possible, setting aside basic road safety elements in their rush for asphalt.

“Contrary to Malaysia or Singapore, authorities did not choose to build separate lanes for motorbikes on the main roads,” says Socheata Sann, road safety programme manager at Handicap International Belgium, a leading NGO in road safety awareness in Cambodia. “This decision has dramatic consequences now. Last year, motorbike drivers and passengers accounted for two-thirds of road fatalities in the country, and the overwhelming majority of lethal crashes happened on national roads.

The road safety perspective is getting more attention now, but progress remains slow and safety standards are still weak, especially for pedestrians, who remain mostly forgotten in infrastructure projects.

If road construction and the boom in vehicle ownership are key factors in the growing death toll, they are exacerbated by weak law enforcement and the fast and loose habits of Cambodia’s drivers. Jumping red lights, driving on the wrong side of the road and drunk driving are just some ingredients of the anarchic symphony that is Phnom Penh, while speeding and daredevil overtaking manoeuvres are the norm on national roads.This Cambodian chaos is far from surprising given that mandatory driving licences for motorbikes – which represent 85% of all vehicles in the country – were introduced just five years ago, while no fines are currently applied to unlicensed drivers.

“Today, only 10% of motorbike drivers have a driving licence,” says Peou Maly, deputy director-general of the Ministry of Public Works and Transportation’s transportation department. “People don’t want to spend $15 to get their licence, and they ride without any theoretical or practical training at all. Many people don’t know the basic rules of road safety, and this becomes a major problem when they travel on national roads or in dense urban areas like Phnom Penh.”

In addition, Peou Maly readily admits that punitive action remains inadequate, offering little in the way of a deterrent. “Today, you can violate the traffic law and get away with a $2.50 fine,” he says. “This is of course a big problem for law enforcement. That is why the new traffic law [developed by the government this year and which is slated to take effect in early 2013] will multiply by five the level of fines. The law will also impose helmet wearing for motorbike passengers and limit the number of people [on a motorbike] to two adults and one child. Controls will be expanded and those who violate these laws will be fined.”

However, Cambodia will need more than a new traffic law to change its drivers’ habits. To have a lasting effect, authorities must address two crucial but very sensitive issues.

Police corruption is certainly no secret in the Kingdom. Many traffic cops prefer to hide in ‘bankable’ spots, where they can easily stop drivers and elicit a bribe for petty offences, rather than enforce the law at dangerous crossings where they could have a positive impact on road safety. Considering their $50-a-month basic wage, this particular police practice can barely be called corruption – survival might be more apt – but its prevalence hinders the educational role that the traffic police should play in road safety.

“Law enforcement and policemen’s wages are a Ministry of Interior affair, not a Ministry of Transportation problem,” says Peou Maly. “In any case, corruption is mostly linked with individual personalities, not salaries.”

The second challenge facing Cambodia will be significantly raising budgets for road safety activities. National and international investment in road safety programmes is currently six times lower than for mine interventions and more than ten times lower than that allocated for HIV/Aids projects.

This lack of investment is a human and an economic nonsense. Last year, road crashes cost the country $310m – $60m more than in 2009 – and research shows that the issue increasingly hinders the country’s development by killing and disabling its economically active population.

“The direct budget for road safety in Cambodia is about $4m,” says Socheata Sann. “Funds have increased over the years, but they remain insufficient given the scope of the problem. Cambodia still lacks a proper financial mechanism to fund its road safety action plan – through taxes on gasoline or driving licences for instance. The country thus remains largely dependent on international donors but few of them support road safety projects. Many still consider road safety an individual issue, not as a public health problem. Funding remains a big challenge, both nationally and internationally.”

By 2020, worldwide road crash deaths are projected to increase by 80%, making traffic casualties the fifth-highest cause of death in all age groups. As one of the poorest countries in Asia, there is little to suggest that Cambodia should be an exception to the rule. In its latest road safety action plan, the Cambodian government committed to reduce road crash fatalities by 30% by 2020, a pledge that will require a sharp acceleration of current efforts. For Cambodia and its development partners, the problem, and its inclusion as a real development issue, is not one that can be pushed to the side of the road any more.