Global stock markets tumbled in August when China’s national currency, the yuan (RMB), crossed the 7 RMB per US dollar benchmark threshold for the first time since 2008.

Seen as a key indicator of the country’s economic strength, the fluctuation came as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted that China’s economic growth would slow to 6.2% from 7.1% last year.

Just last week, the National Institution for Finance and Development, a China think tank, predicted the country’s economic growth rate will slow to 5.8% in 2020, down on a previous estimate of 6.1% for this year and the lowest in more than 30 years. It is the first government-tied body to put the number below 6.0%. To put things in perspective, China’s growth rate in 2017 was 7.8%.

As of August 13, China’s industrial production growth came in at 4.8% year-on-year – down from 6.3% in June and the lowest since February, according to The Trivium Tip Sheet, a Beijing- and London-based market and political research firm that provides daily updates for understanding the political and economic factors in China. Accounting for seasonal distortions, industrial production growth is the lowest it has been in decades, Trivium reported.

The latest figures for retail sales growth in China came in at 7.6% – down from 9.8% in June and the lowest since April. Fixed asset investment growth was 5.1% – down from 6.3% in June and the second slowest growth rate in 2019, after May’s 4.7%.

While many – including the IMF – are quick to point to the US-China trade war as the key catalyst for the slowdown, many economists say that this view ignores China’s deeper domestic issues, which have been years, and sometimes decades, in the making.

“A rapidly ageing population, a falling birth rate, a tightening Federal Reserve and a slowing global economy have combined to put the brakes on China’s economy”

Christopher Balding, Fulbright University

Those issues include a labour shortage, a slowdown in manufacturing, and monumental debt of an estimated $2 trillion that will take much longer to fix than simply coming to a trade agreement with the United States.

A declining Chinese economy is expected to have a knock-on effect on the entire region, something that is already happening in Southeast Asia and forcing countries like Thailand to raise interest rates. Singapore is already looking at negative growth.

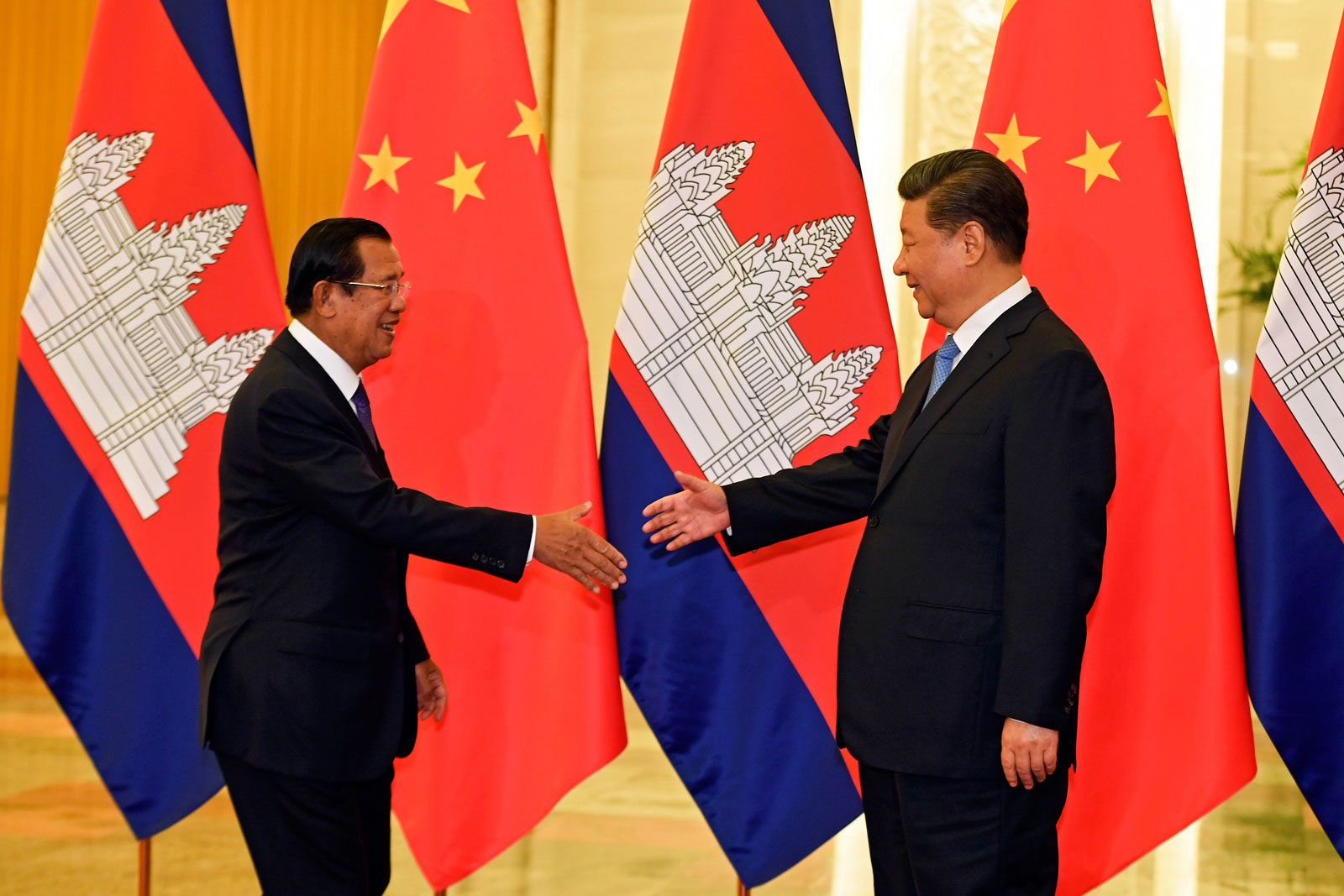

For countries like Cambodia that are heavily reliant on Chinese investment to fuel their own economies, the ramifications could be a major issue as Chinese investment has underwritten most of the recent construction boom in the country.

Cambodia’s growth is projected to shrink from 7.1% to 6.5%, according to a June report by the Cambodian government, which detailed the preparation of a draft financial law for next year.

The report stated that increasing uncertainty and global economic challenges put Cambodia’s economy at risk. Factors contributing to a decline in economic growth, according to the government, include the downturn in the Chinese economy and the negative effects of the China-US trade war.

Long-term problems

“A rapidly ageing population, a falling birth rate, a tightening Federal Reserve and a slowing global economy have combined to put the brakes on China’s economy,” said Christopher Balding, an associate professor of economics at Fulbright University in Vietnam.

Balding says that China’s slowdown began last year when the country experienced its slowest economic growth in nearly three decades. Wage growth has cooled and manufacturers are shedding jobs.

“China’s problems stem primarily from decisions made years – in some cases decades – ago,” Balding said.

“In the past, China benefitted from a growing workforce that boosted GDP (gross domestic product) both by adding workers and because younger workers tend to be more productive than older ones. But around 2012, the working-age population began to shrink, the inevitable result of the [then] one-child policy, which was enacted in 1979. The decline in growth rates owes in part to this demographic winnowing,”

He added that if China’s problems persist it will cause a lot of stress for countries in Southeast Asia.

“There will certainly be a spill-over effect,” he adds.

According to Panos Mourdoukoutas, a professor and chair of the Department of Economics at Long Island University Post in New York, multiple bubbles, including in property, as well as soaring debt, will eventually kill economic growth in the country. Mourdoukoutas compares the situation with what took place in Japan in the 1980s. There are also comparisons with what happened before the housing market crash in the United States in 2008.

“The economic slowdown is already a trend,” former central bank adviser Li Yang, who heads the NIFD, which is affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the South China Morning Post. “We must resort to deepened supply-side structural reform to change it or smooth the slowdown, rather than solely rely on monetary or fiscal stimulus.”

Li said the government’s fiscal deficit problem will stand out in the future, adding that the central government may have to issue more bonds to fulfil its expenditure responsibilities. This could require the central bank to issue more bonds and focus on more coordination and institutional arrangement between fiscal and monetary authorities.

For now, the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, is planning to roll out a national digital currency, which it believes will give the country more control over its fiscal management.

Ting Lu, chief China economist and managing director at Nomura in Hong Kong, says the main goal of a national digital currency would be to strengthen state control over the banking system and the RMB. He adds that it will also allow the central bank to inject stimulus into the economy, something private providers of digital currency in China cannot do.

Right now retail sales are sputtering and asset investment is way down.

“Momentum for slowdown is not yet over,” Julia Wang, an economist at HSBC Holdings Plc. in Hong Kong told Bloomberg. “Given the slowdown is so sharp, it is going to impact maybe the labour market at some point next year, and you are going to see further weakness in domestic demand.”

Heavy debt

China’s central bank has all but indicated that its currency will remain above the 7 RMB figure for the time being, a move that helps Chinese factories offset the costs of the US tariffs. According to many analysts and economists, however, the number is probably where it should realistically be.

“If there is a global economic crisis, it will reduce investment from China and vice versa”

Lim Menghour, Asian Vision Institute

But China’s currency-cutting strategy has the potential to run up an even higher debt load than already exists for China, without the growth to justify it.

China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is hovering at 300%, according to the Institute of International Finance. Fulbright’s Balding says the real number is probably around 330% or higher.

“It’s a problem for China. They may have to make hard decisions and they don’t want to,” he says. Balding says he is personally sceptical that China will let its currency fall further because it is too expensive. “China has $2 trillion of debt. If it lowers its currency by 10% that number goes to $2.2 trillion,” he says.

Chinese tourists pose for the pictures as they visit the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh. Photo: EPA/Kith Serey

Impact on Southeast Asia

While many countries in the region were hoping the US tariffs would lead to more manufacturers moving operations into Southeast Asia, it has been hit and miss.

Some countries like Vietnam have reaped the benefits while poorer countries like Cambodia have not been able to attract as many manufacturers looking to move from China. Even mighty Singapore is sinking into recession after it reported a big drop in economic activity in the second quarter of the year.

And these slowdowns could have a domino effect.

“If there is a global economic crisis, it will reduce investment from China and vice versa,” says Lim Menghour, deputy director of Mekong Strategic Studies of the Asian Vision Institute in Cambodia. “Trading activities and economic growth will be hugely affected.”