In defence of MSG: The seasoning that revolutionised Thai cuisine

Monosodium glutamate, better known as MSG, has a rough reputation in the culinary world for its perceived bad health effects. But this naturally occurring ingredient has simplified and revolutionised the preparation of Thai cuisine, helping to bring good food to the masses

Sitting on the corner of a Bangkok street, I spoon in another bite of the Som Tam papaya salad – the crunchiness of green, unripened fruit, the sourness of the lime, the spiciness of the crushed chili, and saltiness of the fermented fish sauce hit all at once in perfect balance.

For Thais, this would be known as glom glorm taste, a phrase describing when flavours go together well. Or nua, specific to Northeastern Thai cuisine, to describe a smoothness in the seasoning. Whatever the label, it’s representative of the intense heat and sweetness that Thai cuisine has become synonymous with as it has spread around the globe.

The Som Tam is placed on top of a foldable table with Bangkok’s infamously humid heat circulating above the paved concrete. The cook puts together another dish for waiting customers, deftly spooning a scoop of each seasoning into the wooden mortar as an array of white crystals go in, sugar and salt among them.

But also among the white crystals is another essential ingredient, one that has been a fixture in Thai cuisine, and an ever present in Thai restaurants and street food stalls, for more than half a century. Despite this, it’s an ingredient rarely uttered aloud, often excluded from cooking classes, and if raised at all, only with negative connotations: Monosodium glutamate, better known as MSG.

An ingredient first invented little more than a century ago in Japan, MSG has since found its way into cuisines around the world. Though sneered at and frowned upon by food purists, who disregard the seasoning as a shortcut to good cooking and point to its supposed harmful health effects, MSG has arguably transformed day-to-day food for the average Thai, making traditional cooking easier to achieve, both at home and in restaurants.

For Waan Saegratok, an owner of a food stall in Bangkok cooking Thailand’s famous Issan cuisine, MSG is a vital part of doing business, both by stabilising the balance of flavours in her food and reducing the cost of ingredients altogether. The Northeastern Thai cuisine that Waan sells is marked by bold, salty, spicy and sour tastes – she says a sprinkle or spoonful of MSG in dishes can help to seamlessly bring together a dish in a hurry for a hungry customer.

“There’s barely any street food stall that doesn’t use MSG,” Waan said. “Most restaurants along the road, like curry-stalls and order-what-you want stalls, most of them use MSG in their dishes.”

Even before finishing extolling the virtues of MSG, Waan threw in another spoonful of the seasoning into her stir-fry.

“I use MSG just like other seasonings – lime, sugar, and fish sauce. It’s a finishing touch that brings the flavours together.”

MSG’s effectiveness lay in its ability to add umami to a dish, a Japanese term describing the savoury flavour that makes up the final of the five basic tastes – sweet, sour, salty and bitter. While today umami has become a basic phrase in the foodie dictionary, the term was first coined in 1908 by the creator of MSG, Japanese chemist and professor Kikunae Ikeda, after he’d finished developing his synthetic seasoning meant to quickly emulate the taste in Japanese soup stock made from seaweed. To quickly describe the taste of MSG, Ikeda created the new word umami by combining the Japanese words umai, or delicious, and mi, essence.

Despite its negative reputation as an artificial additive, MSG is found naturally in foods such as tomatoes and cheese. While bland on its own, MSG added in dishes dramatically enhances the flavour of the other ingredients – replicating the effects gained from natural cooking methods, such as stewing overnight or selecting a blend of herbs.

But key to the seasoning’s success is its recreation of these effects through glutamic acid – the key component of MSG that brings out a unique hyper-savoury umami taste – and ultimately the simplification of the cooking process.

“Over time, people’s lifestyles have changed,” Wilairat Chinnuam, Thai cuisine chef instructor at culinary school Le Cordon Bleu, told the Globe. “People may have less time to cook – to prepare ingredients and to cook food that tastes good from the essence of the natural ingredients itself. MSG then acts like a helper to make food taste better whilst taking less time.“

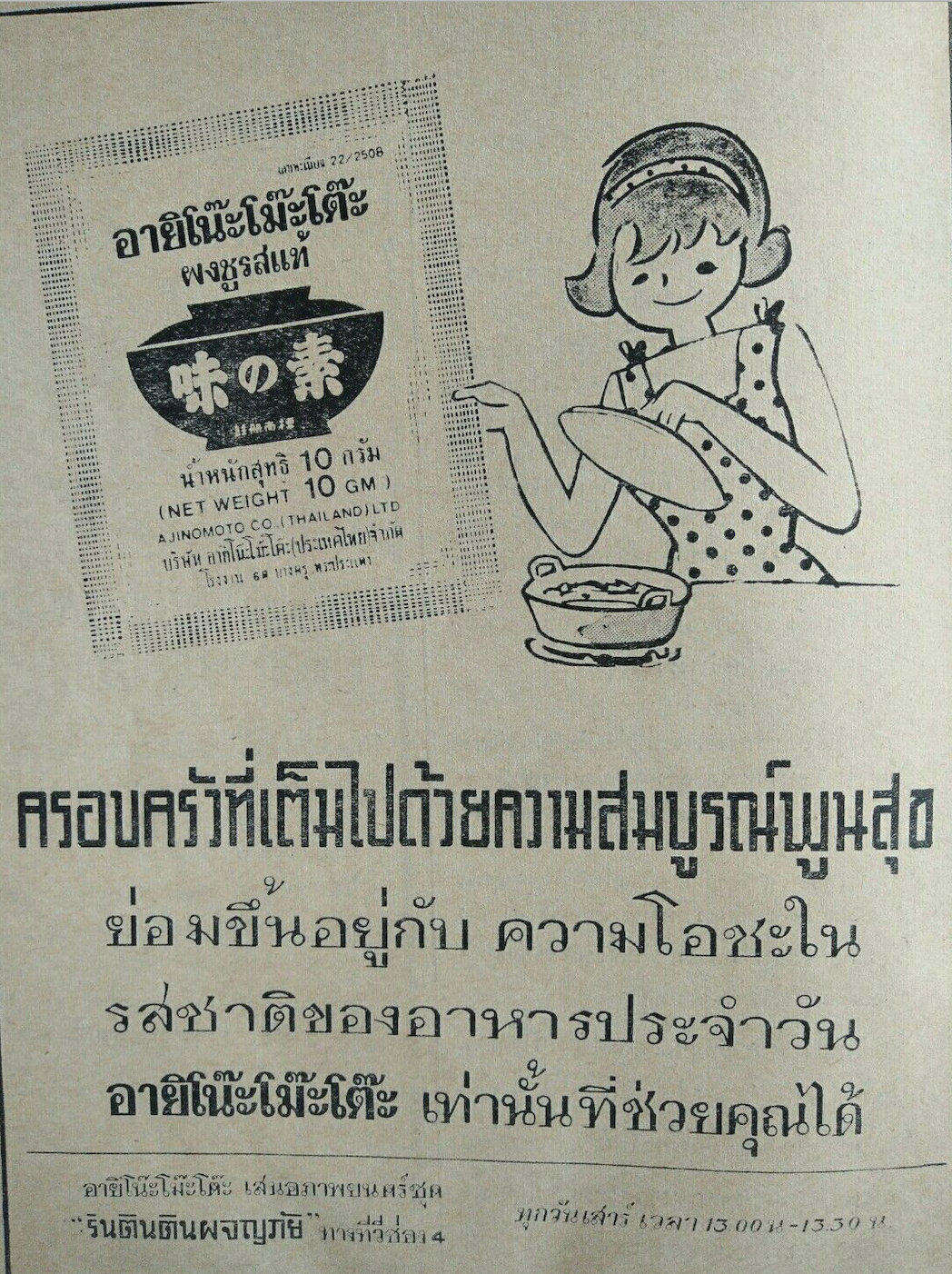

MSG was soon being marketed and sold by the Ajinomoto company, the original brand to sell the seasoning in Japan. In 1959, Ajinomoto began exporting MSG to Thailand. The kingdom soon became the first country outside of Japan to produce MSG for the company, beginning at the Phra Pradaeng Factory on the outskirts of Bangkok in Samut Prakan district.

Although Ajinomoto still dominates the market today, rival brands like Thai Churos, a Thai-owned company, started manufacturing MSG around the same time the Japanese entered the Thai market. Unlike Aijnomoto, Thai Churos aimed their product at a lower price bracket, paving the way for the seasoning to become ubiquitous in working class dishes like papaya salad and helping vendors like Waan generate more income.

But while an innocuous, and even off putting, seasoning for some, MSG is a product that talks to class and economics in the kingdom as higher-income groups use less MSG compared to lower-income groups

Thai consumers needed some time to warm to Ajinomoto’s distinctively Japanese name and foreign seasoning, which the company tried to make more familiar through a heavy marketing and commercial campaign. The original advertisements for MSG on Thai television, produced both by Ajinomoto and Thai Churos, came in a series that aimed to create an understanding of what MSG was.

A Japanese woman, known as the ‘umami teacher’, became the face of Ajinomoto’s MSG product, acting as the messenger for this revolutionary seasoning. Dressed in a light pink button down shirt, with doll-like eyes, and a Japanese accent, she acts as a Japanese language teacher in the commercials – introducing several concepts over different commercials over the years.

In one commercial, the umami teacher explains the flavour of her tasty namesake. In another television spot, she taught Thai students that MSG is made of cassava grown in Thailand.

The commercials brand the new seasoning as a flavour enhancer made from natural ingredients that enables an easier way to cook favourite dishes. The campaign helped normalise the ingredient, transforming it from a new, exotic taste from Japan to a staple in the Thai kitchen. “Umami will become a catchphrase in Thailand soon,” rang one commercial before the jingle of Ajinomoto aired on national TV in 2010.

Today, it is estimated that the Thai MSG market is worth 7 billion baht (around $230 million). Ajinomoto still dominates the kingdom’s market, the largest for the producer in Southeast Asia, with a 70% share of sales. Thai Churos follows in a consistent second, with both MSG mainstays set to taste the benefits of Thailand’s continued economic growth towards high-income country status.

But while an innocuous, and even off putting, seasoning for some, MSG is a product that talks to class and economics in the kingdom. Thailand’s Food and Drug Administration found that higher-income groups use less MSG compared to lower-income groups across the country. The same study also found that over 70% of Thai households and 97% of small to middle size food vendors, especially in street food stalls, use MSG in their food preparation. At about 96 baht (roughly $3) per kilogram, MSG remains accessible to even the poorest in Thai society.

“If people think that they have limited time to prepare food and the selling price is not too high, then using MSG can help to reduce costs by replacing the need to use other ingredients in large quantities to get the same delicious flavour,” said Wilairat.

Time, resources and quality natural ingredients quite often equate to higher cost, exposing the largely unspoken divide when it comes to attitudes towards MSG – those with the ability to lovingly prepare their food, and those, like street hawkers, who must turn over a quick profit.

Skill and attention to detail is highly praised in traditional Thai cuisine. Royal Thai cuisine, the pinnacle of Thai food culture, can take up to days to carve vegetables and prepare ingredients, requiring time and skill for the preparation and presentation of each dish. Even a simple home-cooked broth can require stewing for hours. MSG steps in as an alternative to these steps.

“With the appropriate cooking techniques and time, we are able to pull out flavours of each natural ingredient that is bound to give a delicious flavor in dishes,” said Wilairat. “But, people’s lifestyle has changed over time, and people now have less time to cook. With shortened preparation time to prepare ingredients and to cook food that tastes good from the essence of the natural ingredients itself, MSG is then a helper that makes food taste better whilst taking less time.”

Still, far from a magic ingredient, the reputation of MSG has been spiked for decades with perceived negative health effects. Similar to the so-called Chinese Restaurant Syndrome in the West, there is a wide-spread perception that consumption of foods with MSG can lead to fatigue, headaches, hair loss, and long-term adverse health effects.

But these perceptions are based upon research in which high doses of MSG are injected into mice, a style of consumption that can harm the body but isn’t likely to happen at a local food cart. Most other studies have found MSG to have no proven negative health effects at ordinary levels of consumption.

“If we eat MSG that has passed a certified production process and is hygienic, and we consume it in an appropriate amount – then there shouldn’t be a negative consequence on our bodies and health,” said Wilairat.

Even beyond health, MSG is not looked upon kindly, substituting skill and time, often equated with the amount of care put into dishes as Thai food traditionally indulges itself in intricate methods, diverse ingredients, and patience. But as lifestyles change over time, MSG becomes a substitute for these things, closing the gap between the have and have-nots in access to good food.

With the spread of Thai food around the world, the cusine’s popularity owes a lot to this much-maligned food additive that has become a staple of so many Thai pantries.

“The way I see it,” said Wilairat. “MSG is just an ingredient that comes with the changing times and lifestyle in Thai food.”