Y Kih was from Dak Nong, a province in Vietnam’s central highlands, and belonged to the K’ho ethnic minority. The eldest of eight children in his family, he came to work in Binh Duong Province’s industrial hub earlier this year after his father’s death drove him to search out work to support his mother and siblings.

The 20 year old died from hunger late last month.

“There was a youth, an ethnic minority, he just passed away recently,” Xuan Duong, the project director of the non-profit VNHelp, which has been delivering Covid-19 relief packages in Binh Duong, told the Globe. “He died on August 30 of starvation.”

The southern province of Binh Duong has emerged as the second epicentre of Covid-19 in Vietnam, behind only Ho Chi Minh City in case numbers and deaths. In this wave of the pandemic, Binh Duong’s cases of Covid-19 have gone from zero at the end of May to 179,705 cases and 1,658 fatalities on 21 September.

“He went to Binh Duong to work in a factory in May and then Covid happened and then he lost his job. He was at home without food so he eventually died of starvation.”

Binh Duong is one of Vietnam’s most important industrial zones for the country’s export-reliant economy. To work in the factories, Vietnamese from other provinces flock to Binh Duong to earn a steady income. The province is home to 29 industrial parks, 12 industrial complexes and 1.2 million factory workers. About one in every five residents in Binh Duong was a migrant from another province in 2019, according to a census.

“Binh Duong has a big industrial zone where there are many workers who work in a close setting,” Nguyen Thu Anh, the country director of the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research in Vietnam, told the Globe. “Thousands of workers are working there so it should have been expected that once a few people were carrying the virus from Ho Chi Minh City to Binh Duong you would see a big surge of cases.”

“The number of cases has increased rapidly, very rapidly,” she said.

The province’s migrant workers have been hit hard by Covid-19. Many have found themselves confined to small, rented rooms during the strict lockdowns and are finding it difficult to survive without familial ties in the province and little to no support from the government. Others have had to navigate the overwhelmed medical system and crowded quarantine centres or quarantine within factories to keep companies in operation.

Those workplace quarantine has been dubbed the “3 on-site” model. Workers must eat, sleep and work within their factories, raising concerns about the quality of life for employees and the spread of the virus in tight quarters.

A 27-year-old Khmer-Vietnamese originally from An Giang Province told the Globe he has become very tired living in Binh Duong during Vietnam’s fourth wave of Covid-19. He was recently released from Thoi Hoa Field Hospital, the site of a riot over a food shortage earlier this month where approximately 13,000 Covid-19 patients are quarantined.

He was released from the Thoi Hoa quarantine centre on September 14 but said his wife was still quarantined at the facility where he experienced sparse conditions.

“When I first got there, I didn’t have water to drink,” he said. “I had to beg them to give me a 500 millilitre bottle of water. I only had that water bottle until I was discharged from the hospital.”

“I really want to go home although my hometown is poor but it is not as scary as here …. It used to be so fun here but after this pandemic I feel very afraid of this place.”

Since strict pandemic prevention measures began in June, and have ramped up since, many have lost their jobs and been prevented from returning to their home provinces. With the economic hardship caused by the lockdown, unemployed migrant workers have become one of the groups most in need of support from charities due to little or insufficient aid from the government.

“A lot of workers have migrated from the countryside and they went to Binh Duong to work in the factories to earn a living and now we see, with the strict Covid lockdown, many of them get stuck in a tiny dinky rental place,” Duong of VNHelp said. “They just get stuck in that area without food. They don’t even have a refrigerator.”

Along with larger nonprofits like VNHelp with decades of experience doing charitable work in Vietnam, grassroots efforts are also getting essentials to those in need.

Nguyen Thao was messaging a friend on Zalo, Vietnam’s popular messaging app, when she saw a notification pop up about the app’s SOS function, which was created during the pandemic to allow users to post publicly when in urgent need of food or medical assistance. Reading through the stories, the 32 year old decided to raise money to get food to young families in the province’s capital city, Thu Dau Mot.

Even getting necessities like milk is expensive for those stuck in the province without a source of income, she explained.

“Mostly the people I helped are workers at factories and in construction … they are not from Binh Duong, they are renting rooms here,” Thao said. “I think the people that suffer the most are the people with young kids because it is not easy to get milk and diapers and it is also expensive …. I bought a box of milk for a one-year-old kid and it was 500,000 [Vietnamese dong].”

I don’t have money for rent. I don’t have money for nutritious food…if the social distancing continues, I don’t know what to do next.

The People’s Committee of Binh Duong has pledged to give disadvantaged workers living in boarding houses the same amount Thao spent on a box of milk, approximately $22. But some have been unable to get the meagre cash aid from provincial authorities or the 1.5 million Vietnamese dong, about $65, that the central government promised to provide citizens. For those who have received the funds, it hasn’t been enough.

Hoa, originally from Long An Province in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, told the Globe she lost her job as a kindergarten teacher in Binh Duong in June. Since then, she has been living in a rental room, which is one of her primary concerns along with access to healthy food even though she received government monetary assistance in August.

“I don’t have money for rent. I don’t have money for nutritious food,” said Hoa, who only wanted her first name used. “If the social distancing continues, I don’t know what to do next.”

A Vietnamese economist told the Globe that while in the past those out-of-work would be able to get unemployment insurance, the mass joblessness caused by the pandemic has made it difficult for the government to provide sufficient cash aid to the unemployed.

“Usually you can get four or five million Vietnamese dong per month [roughly $175 – $218] but if they just give 500,000VND or 1.5 million dong it is surely insufficient,” said the economist, who asked for his name to be withheld to protect his career. “The central government hasn’t released those funds yet so these provinces must rely on their own budgets …. The resources of the local government is very limited, even in Binh Duong they cannot give 500,000VND to all workers.”

Thao in Thu Dau Mot heard from a woman trying to get support from the government who was turned away.

“One woman shared the story with me that she lived close by to a place to get some food and some money from the government and she and her neighbor showed up and asked for help and they said, ‘No, I cannot help you because your name is not on the list,'” Thao said.

Although there are incentives for workers quarantined on-site – extra money and the promise of better meals to replace the “famously bad” food factories provide – quarantining within factories isn’t sustainable for the long term. As he said, the cost for companies to keep factories open while following strict procedures like regular testing and hosting employees is too high, while the mental toll on workers is unsustainable.

“The psychology of the worker becomes worse and worse because they need to stay on-site for so long,” he said. “It is like a prison, they cannot sustain it for long.”

Despite the strict measures some companies have taken to keep workplaces in production, there have been outbreaks of Covid-19 in factories in Binh Duong.

At the end of July, 248 of 300 workers at the factory of Long Viet Wooden Tech JSC had contracted Covid-19 despite being quarantined on-site.

At another company in Tan Binh Ward of Di An Town in Binh Duong, AsiaNews reported 600 employees begged to be allowed to leave after 60 virus cases were identified on the premises.

As of August 23, 795 businesses in Binh Duong had stopped having workers quarantine on-site and shut down operations, according to a report. A primary reason was the companies were unable to stop the spread of Covid-19 within the facilities.

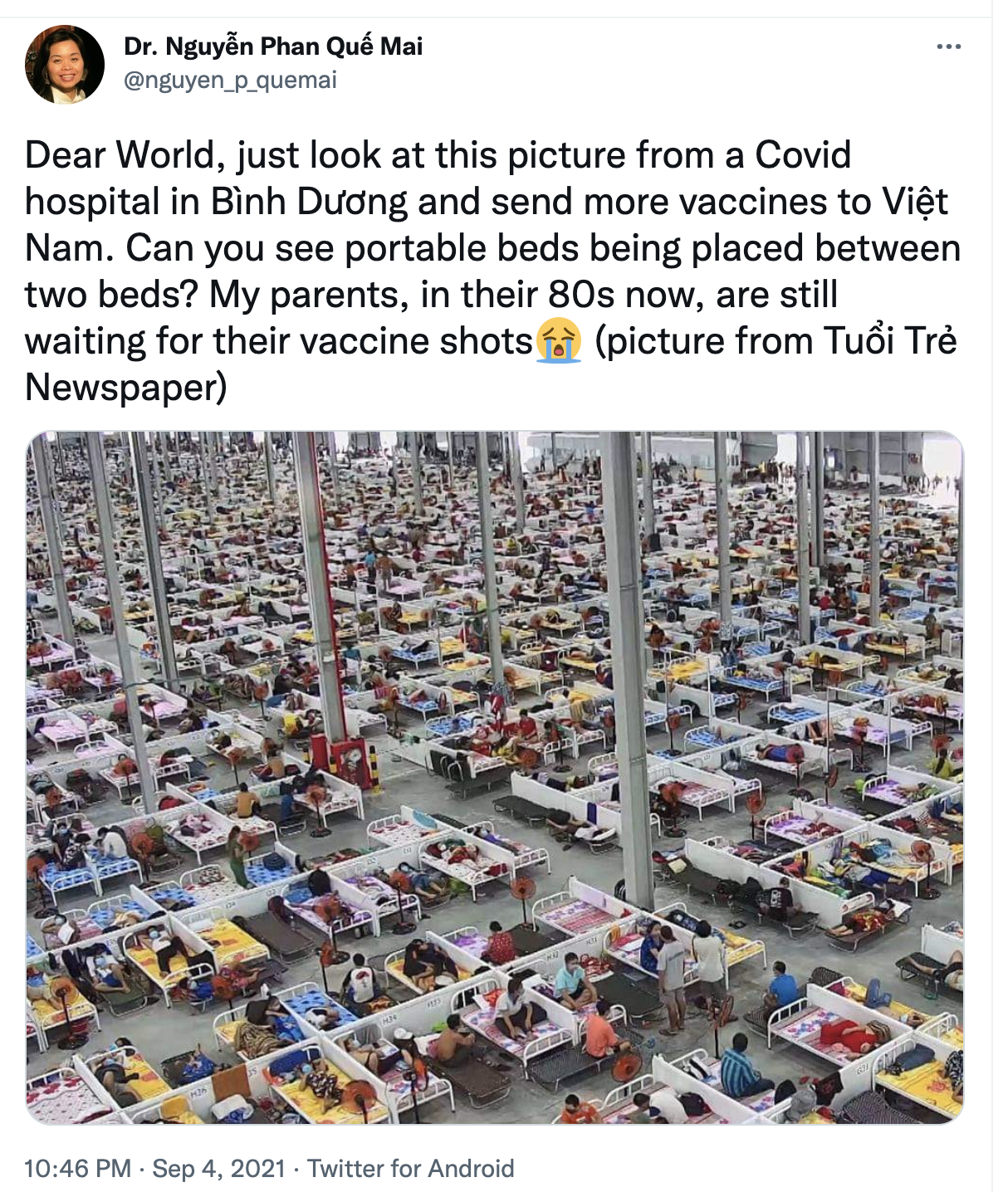

With the rapid spread of Covid-19 throughout the province, Binh Duong’s medical system became overwhelmed.

Thai Duong, who has lost four family members to the virus in his hometown of Ho Chi Minh City, set up a campaign, VietBay, to assist Vietnamese struggling due to the pandemic.

Along with supporting charitable causes in Ho Chi Minh City, VietBay has gotten food packages to Binh Duong workers and Duong has sent supplies to a hospital in the province to treat Covid-19 patients.

“There are tens of thousands of people calling for help in Binh Duong,” he told the Globe. “Two thousand food packages [went] to industrial zone workers in Thuan An and 500 food packages to rubber plantation workers in Phu Giao.”

Speaking with a doctor at a hospital in the provincial city of Thuan An, Duong’s campaign provided items such as 100 portable toilets for patients too weak to stand, towels for frontline workers covered in sweat, pillows to prop up patients and kiwi fruit, which are an easily chewable form of Vitamin C for the sick lacking the energy to eat oranges.

If there are more people infected with the virus, then Binh Duong’s health system will not have capacity to cope

Binh Duong’s death rate has been comparatively low compared to the Covid epicentre in Ho Chi Minh City, which many attribute to the province’s more youthful population. Yet Nguyen Thu Anh of the Woolcock Institute was careful to note the province has also employed methods like early virus detection and mass quarantining, unlike Ho Chi Minh City.

“If there are more people infected with the virus, then Binh Duong’s health system will not have capacity to cope,” she said. “You know most of the doctors and equipment and drugs went to Ho Chi Minh City, so it is very very hard for Binh Duong to increase their capacity in a very short time. The question is whether quarantining all workers and all people who are carrying the virus will help to contain the outbreak. That is the big question to answer.”

While it remains to be seen how impactful large quarantine centres will be to curb the long-term spread of the virus, quarantine centres are clearly overburdened without enough staff.

At a quarantine centre in the province’s Tan Uyen Commune, a riot broke out after a pregnant woman with health complications died suddenly on August 22.

“There was a pregnant woman who had a problem but there was not a sufficient number of medical staff there and it seems she died on the spot,” said the economist who has been closely following the country’s response to Covid-19. “The people there got angry and they got out of control.”

At Thoi Hoa field hospital, where thousands of new patients were brought in early September without management being informed, patients rioted over a lack of food.

“Thousands of new patients, who you could call people who carried the virus, were transferred to that centre and the centre was not informed so they were not able to provide food and different things,” Thu Anh said.

“I think it’s a very sad story,” Thu Anh added. “In Vietnam, not many people die of hunger, we have food everywhere. So it’s not about lack of food, it’s about the management, the supply chain, and how to arrange service in the proper way …. I think there’s no excuse to explain that situation.”