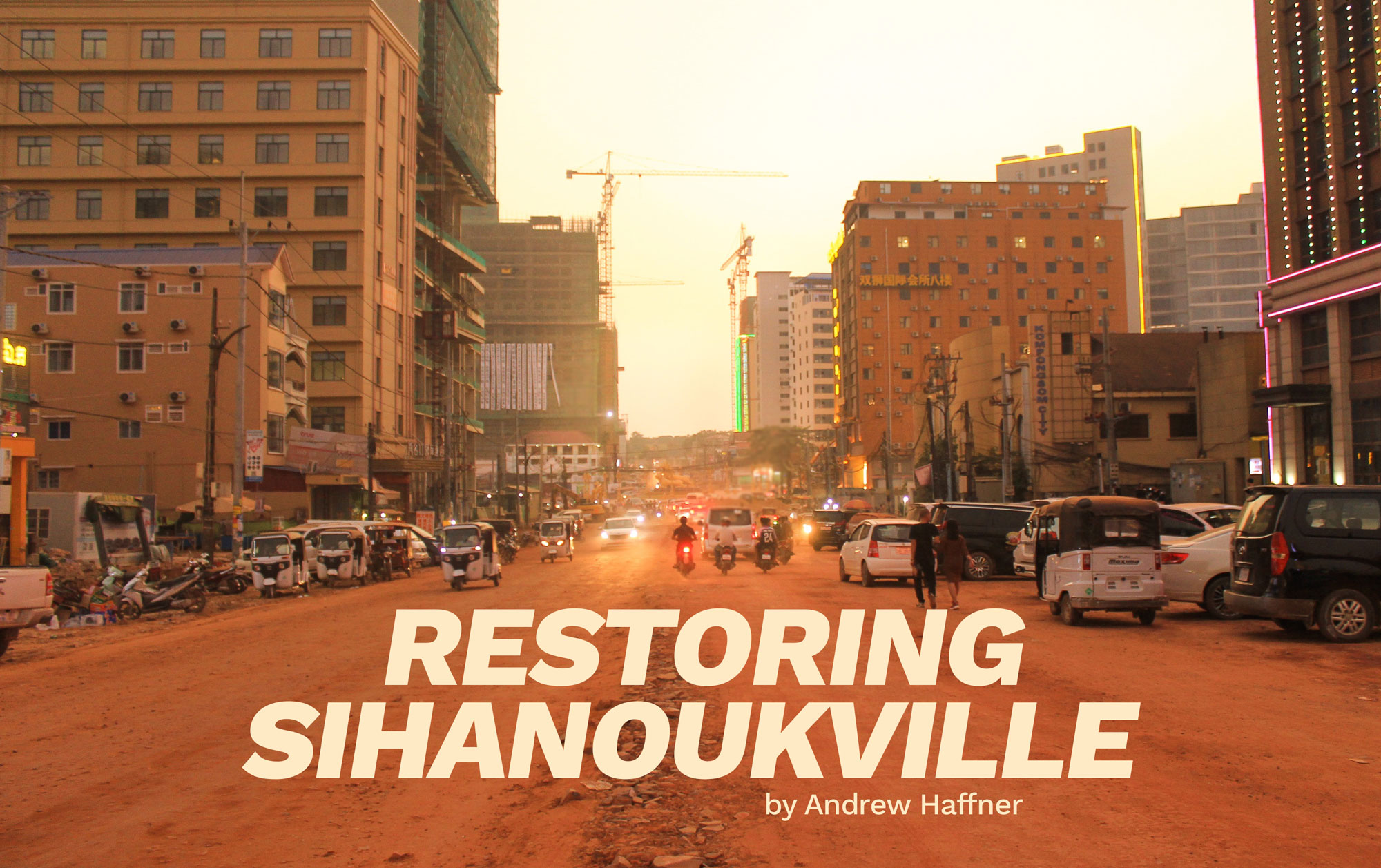

Foreign investors rode a hot streak in Sihanoukville until the gambling game collapsed last summer. Now, with the boomtown at risk of going bust and the city decaying around them, long-term residents, local businesses and construction workers are picking up the pieces

Photos by Andrew Haffner with additional reporting from Molly Bodurtha

Long white banners hang from the green construction netting erected around the shell of an unfinished building. Mandarin characters run down their length, carrying a message for any reader who might pass through the Golden Lions roundabout at the heart of Cambodia’s southern port city of Sihanoukville.

“We have already stopped working for two months, but we have not received compensation for four months of work,” reads the message, apparently written by Chinese construction workers. “Please come to help us. [We believe] that the Cambodian and Chinese governments will support us. Please help decide the future for us workers, and our salary, the wages we earned through sweat and blood, and let us go home.”

The plea flutters in plain sight above the half-completed building, which is just one of many skeletons that make up Sihanoukville’s new but crumbling skyline. For those who didn’t see the sign in person, it made its way online through Chinese social media platforms like WeChat, where users have increasingly discussed the hardships of life in Sihanoukville for their compatriots.

Chinese construction workers are hardly the only ones who have been hit by the city’s dizzying boom-and-bust, a transformation that has accelerated since 2017 on a flood of foreign direct investment.

After the Cambodian government announced its crackdown on online gambling, many construction sites stopped

Ivan Franceschini, the Australian Centre on China in the World

In a past life, Sihanoukville was a seaside holiday town where residents could make a bustling trade on both domestic and Western tourists. A staging area for Cambodia’s islands in the Gulf of Thailand, Sihanoukville also footed traffic for those looking to pass some time before catching a ferry, wiling away sunlit hours in the city’s beachfront bars and restaurants.

That Sihanoukville has largely been replaced, swallowed under a wave of primarily Chinese investment in a new metropolis of hotels and casinos which catered to a bottomless appetite for online gambling back on the Chinese mainland.

However, after the Cambodian government moved last summer to ban Internet gambling – at the behest of Chinese leader Xi Jinping – that investment fervour ran aground, leaving the city beached in a heap of construction debris and concrete shells of now-dubious developments.

As the hot streak went bust on the city’s eager foreign investors, it’s now the local residents – and the workers hanging desperate banners from empty buildings – who are left to deal with the consequences. And ultimately, they’re the ones footing the bill.

Ivan Franceschini, a researcher from the Australian Centre on China in the World, recently finished a survey of 200 Chinese and Cambodian construction workers at six of the city’s building sites.

He told Southeast Asia Globe in a message that the situation described in bold characters on the side of the high-rise was “very common” in Sihanoukville, where many investors fled for home when the chips were down.

“After the Cambodian government announced its crackdown on online gambling in August, many construction sites stopped and a huge number of workers [both Cambodian and Chinese] were left unpaid,” Franceschini wrote. “Some continued working hoping that they would get paid later, others simply left.”

Sihanoukville’s rapid growth buckled the city’s roads and strained its sewage systems under the weight of a population boom estimated to have surpassed 300,000 in 2019. For a city that had counted less than 90,000 residents a decade earlier, this was an incredible turn made largely in just a few years’ time.

But as the casino business lost big under the government online gambling ban, many new Chinese arrivals flooded out of the city, if not the country.

Ben Lee is a founder and partner in gaming consultancy IGamiX, a firm based in Macau, China’s sole legal gambling hub. He became familiar with Sihanoukville during the latest spree while conducting market research for a non-online gambling client investigating the city’s business environment.

“We picked up very quickly that it was not your typical market,” he said.

By the time he finished his research, Lee estimated 85-90% of the revenues made in-house at Sihanoukville’s casinos were from online gambling.

“It was a symbiotic relationship,” he said of online gambling’s role in the casinos. “Because of the turmoil in Sihanoukville, there were actually very few tourists who would [physically] go [there] to gamble.”

It was always hard to pin down the exact numbers of Chinese nationals actually living in Sihanoukville, much less working in the online gambling industry, but Lee said there were rumours within the industry that as many as 300,000 online gambling workers had at some point been employed in the city over the past two years.

Many of them lived in the hotels built above casino floors, or in rented rooms leased out at inflated rates by Cambodian landlords.

They also patronised the businesses that emerged catering to this online gambling workforce – shopping at Chinese retailers and boutiques, and spending time at the karaoke centres, hot-pot restaurants and massage parlours.

Once they left in droves late last year, those businesses were left floundering.

Nikkei reported earlier this month the results of a Chinese business association survey that found 800 restaurants have shut down in the aftermath of the ban. At the heart of the contraction, local media cite provincial labour department data revealing 56 of 75 registered casinos have closed since the ban.

Now, the challenge is on to put the pieces of the crumbling city back together, both to ease local pain and to save face for the upcoming ASEAN Summit, set to be held in the city in late 2022.

While construction on many high-rise buildings has stalled or been abandoned outright, the land below is alive with a crush of activity. As part of a roughly $300 million infrastructure overhaul footed by the Cambodian government, a group of seven construction companies are now at work rebuilding the city’s roads and water drainage systems.

The second part of that overhaul includes a reengineering of Sihanoukville’s canals, a vital system to funnel rainwater – and increasingly sewage and plastic waste – into the sea.

Signs downtown depicting the results of these efforts show an urban core of cleanliness and modernity. But for the time being, while construction is ongoing, the sewers remain open streams along the roadside, the streets are blasted to rubble and dirt, and city dwellers are left to enter their homes and businesses over crude plank bridges spanning the ditches below – many of which are filled with foul-smelling water.

If they complete the roads, but the buildings still look like that – there will be trouble

Vann Sokheng, a businessman and Okhna

Local Cambodian-owned businesses, particularly those in downtown Sihanoukville, have been doubly hit in the past two years, first by spiking rents and then by the turmoil of the ongoing construction effort.

Some of these businesses are improving their odds of survival by banding together in organisations like the Sihanoukville chapter of the Cambodian Chamber of Commerce.

In mid-January, Okhna Vann Sokheng, elected head of the Chamber, opened a roundtable meeting of local business owners to discuss the many pressing matters of the day.

Throughout the two-hour-plus meeting, the gathered Cambodian business leaders focused on the inevitable question of how the city would proceed from its current state of decay. The wide-ranging discussion hit topics such as garbage-strewn beaches and a lingering feeling of insecurity on the streets, a holdover from the organised crime outfits that had worked in and around the gaming industry.

For Sokheng, a businessman with a lifelong career in Sihanoukville and strong ties to the Cambodian government, this is a pivotal moment for the city’s future.

“If they complete the roads, but the buildings still look like that – there will be trouble,” he said looking out the windows of his own building, gesturing to the scene beyond.

His association is focused now on pulling through the crisis by unifying the private sector, all while lobbying the Cambodian government and the local landowners who rented to Chinese investors.

The two men describe their approach as lifting the hurdles to the skyline’s completion.

“Let them finish,” Ly Visal, the Okhna’s administrator, said of the Chinese investment projects. “We want to have a win-win together. We don’t want them to go away and leave us half-built.”

For landowners, Sokheng says the Chamber is asking those who rented to Chinese developers to consider options like forgoing rent for one year to ease the burden of construction.

That’s a big ask, especially for those who relied on that income to pay off their own debt for projects elsewhere. To make that possible, Sokheng is also asking the state to relax taxes on construction materials, in addition to lobbying for extensions to loan repayment periods for those who took on debt to invest in Sihanoukville.

He’s optimistic that such requests will be taken seriously, pointing to the Chamber’s newly scheduled, standing monthly and quarterly meetings with Provincial Governor Kuoch Chamroeun as a signal that the government is willing to engage with the private sector.

Sokheng says that the Chamber’s roughly 400 member companies have also pulled together to explore new sources of revenue to replace the Chinese dollars. So far, that’s included internal partnerships between the Cambodian member businesses to offer package deals to attract more tourism from Southeast Asian countries.

Still, the Chamber’s own estimates show a cratering in demand for space in Sihanoukville. According to their statistics, the city’s once-red-hot casino space was previously selling for as much as $70 per square-metre. Now, the Chamber says, the same space might sell for as little as $5 per square-metre, provided one could find a buyer.

Residential real estate rental prices have also tumbled some 70% from their peak, having a mixed impact on Sihanoukville locals. For those who own property, they’ve lost the inflated rates provided by renting to the Chinese newcomers. But for most others, the drop is a return to much-needed normalcy.

However, the sudden withdrawal of Chinese investment in Sihanoukville’s downtown isn’t universal. Perched on the outskirts of town is the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone, a Chinese concession granted in 2008 to develop an industrial production park with ready access to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative-invested sea-port.

The SSEZ is carved into a flat, sun-baked stretch of land not far from the airport. While roads within the municipality are shredded in the city’s ongoing reconstruction, those in the industrial park are near-pristine stretches of smooth, well-marked tarmac.

It’s within this zone that Jiang Kexing, formerly associated with the SSEZ and current leader of the local branch of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Cambodia, continues to sell his countrymen on the potential bounty of locating in Sihanoukville.

Jiang had come five years ago work on the SSEZ’s development. Now, he says the zone boasts some 165 businesses employing 25,000 Cambodian workers – some of which are newly hired from the roughly 8,000 people laid off from the city’s casinos and hotels.

Speaking in Mandarin, Jiang was keen to distance his organisation and the SSEZ from the turmoil in the city, particularly the construction and casino sectors.

“Casinos often do really bad things to people, and are not in line with our values. Those who have opened casinos here have likely cheated people, promised them fake money, caused a lot of social instability, and caused an array of other problems. So the paths that our businesses and theirs have gone down are very different.”

According to Jiang, the membership of the Chinese Chamber is primarily made up of manufacturing firms who have been largely immune from the boom or bust of the Chinese businesses at the city’s core.

He wrote off Sihanoukville’s casino-centered growth as “more chaotic” than other gambling centres such as Las Vegas or Macau, and said the Cambodian government was wise to limit the gaming industry’s continued growth.

Echoing the promotional material found elsewhere in the SSEZ main office building, he described the city’s ongoing gamble on skyrocketing development as a “painful adjustment period”.

“It’s similar to an illness,” Jiang said of the casino-driven period. “If you diagnose and deal with it earlier, it will be less painful and easier to recover than if you diagnose and treat it later. There will definitely be a painful period, but I would say that in half a year or so, Sihanoukville will be moving forward and on solid footing.

“This isn’t necessarily a bad thing either. The recent developments in Sihanoukville, positive and negative, have exposed areas that were in need of reform; ultimately, things will be better off than they were before.”

If the city truly is fighting a sickness, the medicine will be tough to swallow for many – including long-time residents who’ve lived here since the fall of the Khmer Rouge.

That’s already evidenced in local efforts to rebuild the city to heal the ills incurred during its transformation.

A Cambodian woman living along one of the city’s under-renovation canals said her family was told it would be expanded right up to the edge of her home, eliminating the narrow strip of land atop the bank that provides sole access to her house.

Conversations with provincial authorities had given her little reason to hope for a concession, even though she’d been living at the site since 1985.

She declined to give her name for fear of backlash, but spoke at length at what the overhaul would mean for her living situation along the foul-smelling canal.

“When it’s done, I’ll have to walk to my house in the river,” she said, watching the partners in her small coconut business shuck and clean the green fruits.

A neighbour wandered over to lend her own opinion. Though she’d experienced severe flooding, a now common phenomenon in a city where most of the natural water features had been filled in for development, she was now afraid she’d lose her home altogether.

“They’ve already widened the canal,” she said, looking at the sickly river as it wound through dense housing. “Why can’t they just leave it alone?”