Founded in 1957, Palangkaraya is a city of more than 220,000 people and the provincial capital of Central Kalimantan in the Indonesian part of Borneo. The country’s first president, Sukarno, earmarked it as a possible location for a future capital, due to the area’s lack of tectonic and volcanic activity.

Although the city’s residents remain relatively safe from the pyroclastic flows and deadly earthquakes experienced on the heavily populated island of Java, during late August and early September a different kind of threat emerged to put their health at risk: the smoke from hundreds of fires in the surrounding peatlands.

“Sometimes the sky was clear, but then the haze began to thicken again, until at one point we couldn’t see the sun any more,” said 32-year-old Kartika Sari, who works in marketing and as a volunteer for Gerakan Anti Asap (Anti-Haze Movement). “We didn’t see the sun for two months.”

The atmosphere and landscape turned white and many complained of the same four symptoms: dehydration, irritated eyes, nausea and dizziness. Wearing a face mask did little to help. Kartika found it difficult to travel to meet clients and had to cancel or rearrange appointments after being struck down with vomiting.

Her three-year-old daughter also suffered from nausea, with the added complication of diarrhoea. For children with asthma the situation was much worse, necessitating many visits to outpatient clinics.

“I didn’t allow my daughter to play outside for a month, but even inside the house we could still smell the haze,” she said.

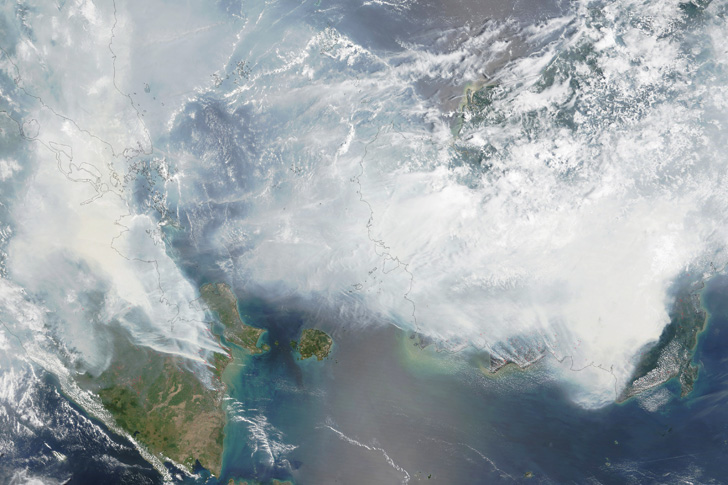

Across Indonesia, from August through September and into October, especially in the provinces of Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) and further west on Sumatra, hundreds of fires sent huge quantities of smoke into the atmosphere. The smoke consisted of a toxic brew of particulate matter and hazardous chemicals – essentially a one-stop shop for respiratory illness. Only time will reveal the long-term effects on Kartika’s daughter and the thousands of other children who have breathed in these fumes.

This year, the situation has been particularly acute, as drought dried out the peat – an accumulation of decayed vegetation that is typically waterlogged but turns into tinder when dry – making it much more susceptible to burning.

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), a global research organisation, the data speaks for itself.

“In terms of the sheer number and extent of fire alerts, this is the worst fire season in recent memory,” said Nigel Sizer, WRI’s global director of the forests programme. “Our analysis shows how massive this year’s spike is, compared to the already-catastrophic levels achieved in 2013. The effect on air quality has been devastating, with more than 500,000 people [on Sumatra and in Kalimantan] reportedly suffering acute respiratory illness and more than 43 million exposed to hazardous air.”

And the problems did not end at Indonesia’s borders. Smoke wafted across the region, causing sporting events to be cancelled and schools to be closed in mainland Malaysia, while plastic screens were placed in mall doorways in Singapore.

In September, Indonesia’s vice-president, Jusuf Kalla, was sanguine about the effects on his country’s neighbours. “Look at how long they have enjoyed fresh air from our green environment and forests when there were no fires,” Kalla said, as reported on news website Tribunnews. “Are they grateful? But when forest fires occur, a month at the most, haze pollutes their regions. So why should there be an apology?”

Erik Meijaard, a conservation scientist who is coordinating the Borneo Futures initiative, said: “The Indonesian government is very skilled at downplaying the severity of the problem by basically denying it.”

There is nothing new in the Indonesian government’s attitude, or in the fires and resultant smoke that plague the country and the wider region year after year. As soon as the land dries out, both small- and large-scale farming concerns light fires to clear peatland in order to plant crops.

Those crops are usually oil palms for the production of palm oil and trees used in the pulp and paper industries. Worst of all, the deadly haze looks set to return unless something changes.

For the small-scale farmers clearing land for subsistence agriculture it is all about education, according to Sizer. “In these cases, to reduce fires started intentionally as a means to clear and prepare farmland, the government can work to educate farmers on alternative land-clearing techniques and provide access to necessary equipment through low-cost microfinancing schemes,” he said.

As far as legislation against the setting of fires is concerned, there is already plenty in place. The problem is that these laws are not being enforced and the political will to deal with it seems to be absent. Indonesia responded well to the 2004 tsunami and managed to successfully crack down on illegal logging in 2004 and 2005, showing that the government can achieve a great deal – when it wants to.

“This highlights Indonesia’s long-standing struggle with poor governance and corruption,” Sizer said of the government’s failure to combat the fires. “In some cases, land mismanagement is the result of conflicts between local farmers and local government over land, confusion over land and resource ownership and responsibilities, or actions taken by politically well-connected or locally powerful individuals driven by self-interest.”

If the will to stop setting fires is absent, perhaps a stimulus from outside would prompt some action. In the case of the pulp and paper sector, this could yield results, said Meijaard. Strong statements from Malaysia and Singapore seem to achieve little, but what did worry the government was when Singapore threatened to ban all imports of pulp and paper products from Indonesia. “Those kinds of things really hurt. The export value combined is $40 billion a year and Singapore accounts for 5% to 10% of that,” Meijaard said. “That’s painful.”

But it is the use of peatland for oil-palm plantations that is the most problematic. Peatland is unsuitable for growing this crop, as it is infertile and too wet. Therefore, fires are lit and chainsaws unleashed to clear forest, while canals are dug to drain water, which leads to the peat drying out.

Often the plantations turn into wasteland but, even before that, huge amounts of carbon dioxide are released, not to mention the loss of biodiverse areas that are home to endangered species such as the orangutan, the Sumatran tiger and the Sumatran rhinoceros.

“Longer term, [the government] needs to recognise that the development of peatlands for oil palm is just not an option,” said Meijaard. “Ultimately, it’s totally unsustainable and will lead to recurring episodes of these fires and the release of large amounts of greenhouse gases. That will require a lot of political commitments because a lot of money has been involved and already invested.”

Back in Palangkaraya, Kartika is pessimistic about what lies ahead. “I’m pretty sure the haze will happen again,” she said. “The situation is much better today, but it’s because of nature. It has been raining with high intensity for a week. That’s not because of strict law enforcement, so the haze is very likely to happen again in the future.”